Some mountain climbers talk about “conquering the mountain”, but that simply is not true at all. If anything, it is more a test of wills, and the mountain’s will is rock solid – having been forged over millions of years. In reality, climbing a mountain like Kilimanjaro is a tremendous personal challenge. The mountain knows all about its capabilities and limitations, but the question is.. do you? You will find yourself tested in ways your never considered until now. The mountain demands much of you – commitment, desire, toughness, patience, physical and mental endurance. But what do you demand of yourself?

In the morning of the First Day of my climb i met my guide, Samuel, and our porters, Nechi, Avoit, and Reginald.. that’s FOUR humans tasked with assisting me with my climb – wow! As we drove around town collecting the final goods needed for our trek, i asked Samuel how long he has been climbing the mountain. With a big smile, he replied “22 years!” When he got out of the truck to buy some meat i saw that his calf muscles were carved from stone and i knew that it was true.

We drove to the base of the mountain and checked in at the Machame gate. I filled in the registration logbook and looked over the recent entries. Almost ALL the climbers were from various European countries. On four complete pages of names i saw only three Americans. Beautiful.

At the Machame Gate.. let's Rock n' Roll!

At the Machame Gate.. let's Rock n' Roll!

I began the first day’s climb through the rainforest with Nechi while the others checked in at the gate and weighed our gear. As we talked Nechi told me about his family. He is the 5th of 6 children, though his father has two wives and a total of nine children. I asked him if this was common in Tanzania and he said yes.. sometimes more than four wives to one man! However, you must pay a dowry in cattle for each wife, so only wealthier men can have multiple wives. Then he asked me, “Can you have more than one wife in America?” I replied, “Unfortunately, no.. unless of course you live in Utah.”

The first day's climb through rainforest was gorgeous.

The first day's climb through rainforest was gorgeous.

Day Two of the climb began the same as most days. Wake up at 7 am. At 7:15 i am given warm water and soap to wash my hands and face. This is followed by breakfast, which usually consisted of porridge, a few slices of bread, some cucumber slices, fruit (orange or banana), an egg, two sausages, and tea. When i am done, Nechi would come over and ask, “Fee-nished?” And i’d respond, “Ndiyo, kwisha. Asanta sana.” – Yes, I’m finished. Thank you very much.

Weather permitting, my usual breakfast setup.. table for one!

Weather permitting, my usual breakfast setup.. table for one!

On the second day i met a very nice Dutch couple on the trail. I told them the very best method for breathing and how to treat the wife’s ailing knee. They greatly appreciated the advice and offered me a cookie.. thus we became immediate friends. Whenever we’d see each other on the trail we’d stop to chat and share sweets. As we sat for lunch we saw two porters running down the mountain and found out that a climber was being evacuated from the mountain. We chewed a little more slowly after that.

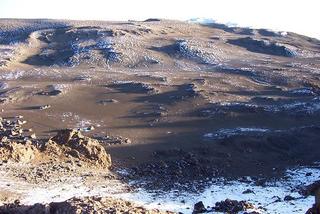

My god.. WHAT planet am i on??

My god.. WHAT planet am i on??

“Pole pole” (slowly) became more than just words, it was a mantra. In order to improve your chances of success (and avoid altitude sickness or death) one must walk painfully slow for hours on end. It may not sound like much, but this is EXTREMELY difficult.. especially for an American. You must also breathe slowly and evenly – the ultimate exercise in meditation. Indeed, my experience meditating was a tremendous advantage, allowing me to focus my breathing and remain patient. Breathe in. Step left, right pole. Breath out sloooowly. Step right, left pole. Hydrate. Repeat. I became acutely aware of my heartbeat, body temperature, hydration status, and my body’s calls for more oxygen (yawns, lightheadedness, headaches). There isn’t mush time to think about anything else.

Truly.. the porters are Gods among men!

Truly.. the porters are Gods among men!

Before the climb i underestimated its difficulty. I thought the days leading up to the summit night would be fine, with the real difficulty coming at the very end. I was wrong. Each day presented its own challenges and as we climbed higher the difficulty level multiplied. I knew that the altitude adversely effects your appetite, so i began the trek attempting to eat everything placed before me. But by the end of day three, i was already forcing myself to eat and could never finish all of my food. Still, each time the clouds parted and the summit appeared i was driven forward. Seeing the vegetation change before my eyes as i climbed was incredible. This challenge was not without its rewards.

The clouds reveal the summit.. pushing me on, so close, yet still 10,000 feet away!

The clouds reveal the summit.. pushing me on, so close, yet still 10,000 feet away!

Day Three was the most difficult thus far. The initial climb was long and tough with a large elevation gain peaking at 13,500 feet. It got worse as the weather turned - first bitingly cold wind, then hail, and eventually driving sleet. I did not expect this, as it was sunny and warm in the morning, so I did not have my gloves with me. My hands froze and fingers began going numb. I borrowed some gloves from Samuel, but my fingers were still numb, so i wrapped each hand carefully in a bandana. Luckily the rest of the day was downhill to camp and went quickly. However, i ended the day with a massive pounding headache.. the first symptom of altitude sickness.

The daunting Barranco Wall.

The daunting Barranco Wall.

The morning of Day Four i felt much better, the rain/sleet had stopped and my headache was gone. The beginning of the day’s climb however, was up the sheer face of the Barranco Wall. Just looking at it you cannot imagine that it is even traversable. The “trail” consisted of clamoring over rocks and some rock climbing – i loved it.

Scaling the Barranco Wall.. a little rock climbing anyone? It was awesome!!

During the day’s climb, Samuel and i would stick together, while the porters would finish packing up camp only to surpass us on the trail later so that they could begin setting up the next camp before we arrived. Samuel set the pace by leading, reminding me “pole pole” and stopping occasionally to ask, “Habari, John?” – How are you feeling? I’d usually reply, “Mzuri sana, asante. Twende.” – i’m doing very good, thanks. Let’s keep going.

When we reached Karanga Valley, Samuel showed me where the old campsite had been, explaining “The weather is very bad here and many people were dying in the night, so the rangers moved the campsite to the ridge.” I was glad that to be here after they figured this out.

My wonderful porters and guide - Reginald, Nechi, Avoit, and Samuel.

When i would see porters or other mzungus on the trail i was always sure to greet them in Swahili.. “Hujambo!” – Hello, or “Habari?” – How are you doing? This usually elicits a hearty response from the porters and a confused look by the other mzungus. All of the other climbers i’ve met are very surprised to hear that i am here alone, but that’s a badge of honor for me. Four friendly Germans rolled by on the trail before recognizing the wisdom of my pace and adjusted themselves accordingly.

Patience and even breathing will get you through this desolate landscape.

Patience and even breathing will get you through this desolate landscape.

On the evening of the fourth day, i went outside to gaze up at the stars. With the clouds now gone, the half moon cast a soft glow on everything. Spread out far below lies the twinkling lights of East Africa. Above me, the peak of Kilimanjaro strands in grand majesty, its glaciers pure white in the moonlight while the rest is covered in last night’s new snow. I take it all in for a long time. It is one of the most beautiful things I have seen in my entire life.

In the morning of Day Five, we received some discouraging news. Of the four Germans who started the climb the same day as myself, two had had enough and were forced to begin their descent. The other two, more fitter Germans pressed on and made an attempt on the summit the previous night. Unfortunately, they failed in their attempt after only making it halfway. I pushed this from my mind so that we could reach the Barafu base camp at 15,100 feet and get some rest before my own attempt on the summit that night.

Making the final drive to the summit base camp.

As i lay in my tent trying to get some rest at Barafu camp, i was woken by loud chatter and shouts among the rangers. I asked Nechi what the commotion was about, and he said a German man had fallen badly on his way to the summit, breaking his leg. The "rescue team" was deployed, which consisted of four men and a stretcher balanced on a bicycle wheel. I later found out that it took ten hours for them to get him down the mountain and to a hospital. But i couldn't think about that now.. in just a few hours i would be making my own drive for the summit.

The 'ambulance crew' rushes up the mountain to collect the victim.

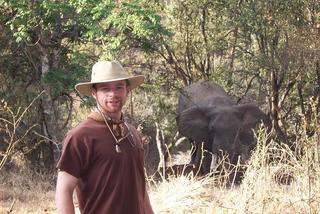

myself and Kilimanjaro.

myself and Kilimanjaro.